It wasn’t really a tornado the way Sandy wasn’t really a hurricane, but for those who experienced the weather event that hit Gardiner around 5:00 pm, Friday, June 12th, this would seem like splitting hairs. By the time the sun reappeared 15 to 20 minutes after the first rumbles of thunder, a swath of Gardiner was a tangled heap of downed power lines, mangled trees and property destruction of all kinds.

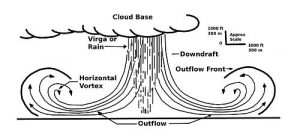

Known as a downburst, the storm descended on a section of Gardiner roughly bounded by Sand Hill Road on the east and Burnt Meadow Road on the west, encompassing Albany Post in between. A downburst, a column of exceptionally intense sinking air encapsulated in a thunderstorm, results in a violent outrush of air at the ground and is capable of producing straight-line winds of more than 100 mph. According to Steve DiRienzo, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service (NOAA), microbursts are up to 2 1/4 miles in width, and macrobursts are more than that. Gardiner’s downburst had a footprint of 2 1/4 by 2 1/4 miles, so “it was right on the fence between a micro and a macro,” he said.

Our forecast area (19 counties in eastern New York and western Connecticut) gets hundreds of downbursts each summer, most of which “fall in unpopulated areas and go largely unnoticed,” DiRienzo added. The winds in the Gardiner downburst were recorded at 90 to 100 mph, making it the equivalent of an EF1 tornado (86–110 mph). “We had trees into houses and trees on top of houses,” said Highway Superintendant and Assistant Fire Chief Brian Stiscia. Power poles dropped across Burnt Meadow Road like pick-up-sticks. In the Hamlet, the tents from the Farmers’ Market shredded. There was a trampoline in a tree; a man told of his car being lifted with him in it; parts of McKinstry Road and Albany Post were cut off, with all access roads blocked by storm debris. The strongest downbursts are the equivalent of EF2 tornadoes (111–135 mph).

As for why the destruction was so localized, the thunderstorm that day was moving from west to east, so the downburst picked up some momentum, but in the absence of movement from the overriding storm a downburst literally “sits down” on an area. As a result, most of Gardiner was untouched, unaware that chaos reigned nearby.

By 6pm, Brian Stiscia had conferred with Town Supervisor Carl Zatz and Zatz declared a state of emergency. In this instance, it resulted in the closing of unsafe roads and the redirection of traffic; in other types of emergencies (such as flooding) forced evacuations and, in extreme circumstances, the implementation of a curfew are possible. (Declaring a state of emergency may also make the town eligible for certain state funds when damage is eventually assessed.)

A command center was set up in the Fire Station. By midnight, Central Hudson had twelve crews here. Because of a mutual aid arrangement already in place, the Gardiner Highway Department and Gardiner Fire and Rescue were joined by the Fire Departments of Wallkill, Modena and Shawangunk Valley, all coordinated by Stiscia in consultation with Zatz. NOAA sent a representative. Zatz stayed in touch with the Director of Ulster County Emergency Services throughout. The ladies Auxiliary stepped in and took care of feeding the emergency responders. The private sector also leapt into action; the family on Sand Hill Road with the crushed car and house said they don’t know how word got around, but “a large group of skydivers showed up wearing gloves.” They worked for a day and a half.

It was like a siege, and those of us affected were hunkering down for a very long one. Unbelievably, roads were cleared and power restored within 26 hours and, by 9:00 Sunday morning the state of emergency was lifted.

We were also very fortunate in other ways. In a list of “notable microbursts” on Wikipedia, three were in the Northeast: on July 15, 1995, a series of microbursts hit eastern New York State, killing 5 people, injuring 11, and causing nearly a half billion dollars in damage; on September 7, 1998, a microburst hit the city of Syracuse. Three people were killed and the area suffered $130 million in damage; and on September 16, 2010, a macroburst in Queens, NY, killed a woman when a tree fell on her car. In Gardiner, Brian Stiscia said, “An outrigger from a truck came down and crushed the foot of a Central Hudson worker.” It was the only injury he knew of.

A cross section of a downburst. Photo courtesy the internet.

Gardiner’s response after the event was an extraordinarily successful test of our planning practices. “Among other things, we assess likelihood and severity,” Carl Zatz said. “For example a propane facility blowing up is a much more severe situation, but the likelihood is very low. A storm of this kind is less severe, but much more likely. It helps us make decisions about whether we’re going to spend money on equipment to fight propane fires, or on chain saws to clear downed trees.”

As for what to do when it’s happening, Steve DiRienzo at NOAA said, “if there is a thunder storm you should be indoors anyway so, for a downburst, absolutely, be indoors. Stay away from large picture windows. Don’t be upstairs where a tree can more easily fall on you.” For those unlucky enough to be outdoors on foot or on a bicycle, etc., he said “Get inside. Knock on someone’s door if you have to.”