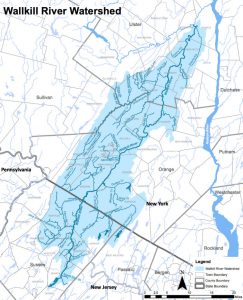

Wallkill River Watershed

There was an excellent turnout when the Wallkill River Watershed Alliance held its fifth Wallkill River Summit on May 16 at SUNY New Paltz. It featured speakers Brian Duffy of the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and Riverkeeper scientist Jen Epstein. Until attending the meeting, I had no idea of the significance of the Alliance and the work that it does to help clean and preserve our River.

The Alliance has as its motto, “We Fight Dirty”; very apt, for dirty is one way to describe this important tributary of the Hudson River. And the Summit’s topic this year was “How’s the Water?,” which has a very simple and direct answer: “Not good!”

Consider that the Wallkill is the largest estuary of the tidal Hudson, from its rise in Sparta, NJ, until it merges with the Rondout 88 miles later, near Kingston, where it flows into the Hudson. Along those many miles the river has 20 municipal wastewater facilities, which need more than $70 million in documented needs for collection system and plant repairs and upgrades.

Think about the following: the EPA threshold for swimming is 60 entero fecal-indicator bacteria per 100 mL of water; at Goshen’s Rio Grande tributary at Heritage Trail, the entero count is 1,213, and 0% of the river water there is safe for swimming. At Gardiner’s Shawangunk Kill, it’s 90% unsafe, with a count of 440. Only at Tillson, below Sturgeon Pool, is 52% of the water safe for swimming. In other words, the Wallkill is considered to be impaired, according to the Impaired Waters List under Section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act.

A significant problem is that treatment plants are not required to remove nutrients from treated effluent, and these nutrients feed harmful algae blooms, among other undesirable biota. Phosphorus (think detergents) and nitrogen are the main culprits here, and the State doesn’t even have up-to-date criteria to accurately assess water quality in the Wallkill, let alone the entire state. Additionally, arsenic and DDT still affect the water, long after being banned from agricultural use.

Hence, the DEC announced at the May meeting that the Wallkill is to be given monitoring priority to determine its Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) of nutrient levels, particularly phosphorus, which will become the river’s “pollution diet,” in the words of Dan Shapley, Water Quality Program Director for Riverkeeper. This entails, but is not limited to, upgrading wastewater treatment plants and encouraging farmers to reduce runoff by planting crops right up the banks of the feeding streams.

The Wallkill watershed covers 800 square miles and includes 42 cities, villages and towns in New Jersey and New York. There are countless streams, small and large, such as the Shawangunk Kill, that feed into the Wallkill, carrying with them stormwater and other effluents from these 42 communities, all of which contribute excess sediment, bacteria, and pesticides.

The Alliance is exploring the formation of a Stormwater Coalition to help municipalities comply with Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) standards. Gardiner is one of 19 local governments that already participate in MS4 regulations; 23 more need to join.

In fact, the Alliance needs our support. You can, for example, call your state legislators to tell them what the Wallkill means to you, and that you support legislation such as the 2017 New York State Clean Water Infrastructure Act, which provides grants to municipalities to help them improve water quality by upgrading wastewater infrastructure. Ask what they are doing to draw grants to towns in the watershed, such as Gardiner and New Paltz. Attend monthly membership meetings to learn about ongoing projects and to become involved in volunteer work. You can make a donation and become a member at https://tinyurl.com/wallkilldonation. Sign up for the newsletter by sending a blank e-mail to wallkill+subscribe@google-groups.com.

We can all help restore our river so that it is once again safe for swimming, canoeing, kayaking, and other water activities, as well as make it safe again to fish. (There are 22 known species in the river, most of them edible if taken in clean water.)

My own family has a farm on the river with almost a mile of frontage. We had a watering hole in which we could swim until about 15 years ago—not knowing that it was already becoming dangerous.

Perhaps our grandchildren and their offspring may be able to swim once again. May yours join them!