Climbing Before the Vulgarian Revolution

By The Gazette Editorial Committee

From Issue 12: Fall 2011

Editor’s Note: This is part two of a two part series. In Part One, former Gardiner resident and experienced climber Louise Trancynger discovered the now-fabled climbing cliffs at the Gunks, but also discovered that since the 1940s they had been controlled with military precision by elite members of the Appalachian Mountain Club, known as the “Appies”…

In 1956, my first spring at the Gunks, I made an attempt to lead a few easy climbs, but the rules were dishearteningly frustrating; two qualifying leaders had to gualify me for each climb. Pitons already lined the routes and basically all I had to do was tap each piton with my hammer to ensure it was secure, clip a carabineer through the piton, then run my rope through the carabineer and secure the party at each belay ledge. A number of leaders judged me and approved that “first leg,” but I never was successful in getting anyone to test me for a “second leg” to lead even one of those climbs.

Most Appies considered the cliffs preparation for climbing mountains. Organized weekends occurred only during the spring and fall, with many climbers going off in teams to conquer their mountain of choice during the summer. When organized climbing ended I wanted to continue climbing weekends. Fortunately, Krist Raubenheimer, her husband Wally, and Ted Church remained at the Gunks that summer. Though they were the nucleus of the power structure, I liked Wally and Ted, and they gave me the opportunity to climb many of the hardest climbs at that time. We teamed up almost every weekend. Ted, who usually belayed me, often laughingly said, “You’re cheating. You made that move look too easy.”

I met Jim Andress, an outstanding athlete, artist and musician, early on in my time at the cliffs. We clicked. He was turned on just being at the Gunks, let alone climbing. Jim had served with the 10th Mt. Division during World War II and trained at Camp Hale, Colorado. There, the troops rock climbed, skied, engaged in mountain rescues and were pushed to their limits. Late in the war two platoons scaled a cliff in Italy in the moonlight to surprise the Germans, who never imagined our soldiers, weighted down by heavy equipment, could reach the top. The fighting was fierce month after month. Jim, a medic, became litter squad leader each time his leader was killed, but kept losing his stripes for failure to follow orders he believed were unwise; flawed orders had resulted in the deaths of some of his buddies. However, when he joined the Appalachian Mt. Club, he was eager to respect their rules. He loved the friendly interaction of interesting, dynamic people, especially the camaraderie at the end of the day at Schleuter’s boarding house, just down the road from where the Mountain Brauhaus House stands today.

Jim and I started dating about the time my “mommy urge” surfaced. In those days, a single girl of 24 was considered close to becoming an old maid. Jim and I had a lot in common, especially when it came to active sports. In the winter of 1956 Jim switched from his seasonal job in construction to the job he loved: ski school instructor at Belleayre Mountain. I skied every weekend with Jim’s friends while he taught, then we crowded into restaurants for food and fun, just the way we did at Schleuter’s. We eloped at the end of the season.

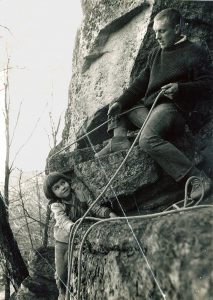

Dave Craft leading Louise’s first daughter, Susie Andress (around age five), up a climb in the Gunks. The climbing Susie did was much more challenging than what you see in the picture and she thought this was a lark.

We showed up as man and wife for the first Appie spring climbing weekend at the Mohonk Mountain House. Our room was crowded with partying well wishers, with so many people sitting on our double bed that the bed crashed to the floor. Yet, not one of my new friends in the inner circle of leaders was there to celebrate with us. Had I broken some rule by marrying Jim Andress?

After breakfast the following morning we assembled under the cliff with our climbing gear. The leader for the weekend assigned each team: a leader, second to belay the leader, and one or two more climbers. When he finished, Jim and I had been left out. “So,” Jim asked the leader, “Who are we going to climb with?” The response was, “You’re not. You’ll have to wait until we get back.” They left.

We were stuck in an Alice in Wonderland moment. Our predicament was absurd! Stunned to be told we couldn’t climb, Jim quietly expressed his dismay. In an upbeat voice, I immediately responded, “I’m going to climb.” “How are you going to do that?” Jim asked. “You’re going to take me up something,” I replied. And he did.

Jim was on the first belay ledge of “Gray Face” and I was halfway up the pitch when Wally Raubenheimer approached from below. “What are you doing up there?” he called. We laughed, “We’re climbing.” He marched under us and demanded, “Come down from there!” We laughed again and kept climbing.

I can’t remember formally climbing with the Appies after that. Jim put up the climb “Handy Andy” with me as his second. I also vividly remember the two of us climbing “Andrew” with Hans Kraus. Hans led, Jim was next and I brought up the rear. It was an easy face climb, which meant if you relied mostly on your feet, you could cruise up, feeling like a ballerina dancing up the cliff. I’ll admit I was showing off, attempting a flawless performance with minimal pauses. I was ready to climb over the lip of the cliff when I heard Hans’ stern voice directly above me, “You are an unsafe climber. You should have three points of contact with the rock at all times!” This time I kept my amusement to myself.

Art Gran, who would create the first formal guide book to the Gunks in 1964, was bringing City College of New York students to the cliffs. Just enthusiastic climbers to begin with, most developed into Vulgarians. 1956 was the year 19-year-old Dave Craft showed up. He was another local, like me, who discovered climbing at the Gunks on his own, while hunting. I can remember Dave, totally awed, returning from the first ascent of “Yellow Belly,” which raised the bar above the hardest climbs achieved by the Appies. Jim McCarthy led that climb, and pursued a string of challenging first ascents. Jim would continue to be respected in the Appie organization in spite of climbing with the Vulgarians as they became more revolutionary in climbing, as well as socially outrageous, like tipping over a Volkswagen bus.

Exasperated by the tight control the Appies had over every climber at the cliffs (they issued all the climbing permits), Dave Craft asked Gerow Smiley (a member of the Smiley family who owned the Mohonk Mountain House and the cliff property at that time) if climbers could get permits directly from Mohonk. One day Gerow handed Dave a batch of climbing permits; the Appies no longer had total control over who climbed with whom, when, and where.

We still loved going to Schleuter’s. Margo ‘s masterpieces (like her mouthwatering sauerbraten and Black Forest cake) never disappointed, and Jim McCarthy and Jim Andress entertained us with push up or sit up competitions. Andress went first … McCarthy would always manage one more. I remember this scene: Jim and I were at the bar talking to Margo, serving as bartender. Jim placed our first daughter on the bar. She had inspired the name for the climb “Susie A.,” put up by her father and Roddy Miller. Margo was amazed and delighted when Jim got ten-month-old Susie to do a sit up. (Exercise guru Bonnie Prudden had given us one of the early books she coauthored with Hans Kraus, President Kennedy’s orthopedic doctor, advising parents on physical fitness for children. Inside the cover Bonnie had written, “To Susie, who probably doesn’t need this book.”)

At the time, no one thought to call me a Vulgarian, even if I had sown one of the original seeds of the rebellion. It was Jim who developed into an enthusiastic Vulgarian while I was busy taking care of babies: our second daughter, Mary Lou, arrived the day before Susie’s first birthday, and our youngest, Carrie, ended my “mommy urge” a year and three months later. Still, just like Eve, It was I who had tempted the man.

2 comments