“Gone to his long home,” is how a local New Paltz newspaper, on August 28, 1863, described the death of Gardiner resident Michael Malady. He had been a private in the 156th New York State Infantry for about a year when he died far from home.

“Gone to his long home,” is how a local New Paltz newspaper, on August 28, 1863, described the death of Gardiner resident Michael Malady. He had been a private in the 156th New York State Infantry for about a year when he died far from home.

An immigrant from Ireland, he was born sometime around 1822. Once in the United States, he eventually made his way to what is today Gardiner. Malady lived in the close-knit settlement called Libertyville with his wife Bridget. According to the 1860 Federal Census, Michael was a laborer struggling to make ends meet, supporting a growing family.

Yet Malady joined the 156th Infantry Company A, on August 19, 1862. Lt. P.A. Lefever was the enlistment officer. Like many immigrants of that era, he probably joined for the $25.00 sign-on bonus which lured many soldiers to volunteer. Furthermore, a steady paycheck of $13.00 a month could be sent home to his family.

It also appears, by a notation in his military records, that he was, what was called at that time, a “substitute,” a person legally hired by another to serve in the army in his stead. Such payment could be as high as $300.00, and this practice was a legal option at the time. No doubt the money that Private Malady earned for enlisting was probably more than he had ever seen at one time.

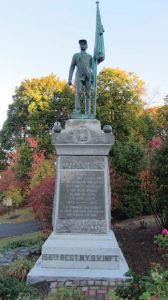

After joining the 156th, he was mustered in on November 17, 1862. His enlistment record describes the 41 year-old Malady as having “blue eyes, brown hair and a sandy complexion.” He stood at 5’7” and was listed as Class 3. This designation meant that he was a volunteer. According to the regimental history, Colonel Erastus Cooke recruited soldiers for the 156th regiment in Kingston. Soldiers like Malady signed on for three years. The 156th was composed of different companies, but Malady’s Company A, “was recruited mainly from Plattekill, New Paltz, Gardiner and Shawangunk.”

So, Private Malady was with his neighbors and friends, which may have provided some comfort for him.

The regiment set sail for New Orleans on December 4, 1862. The 156th became part of General William T. Sherman’s Division, Department of the Gulf. Private Malady’s company saw their first battle during the battle of Fort Bisland which lasted from April 12 to April 13, 1863.

Next, he saw action in the Siege of Port Hudson including an assault on June 14, 1863, where the officer leading the charge, Lt. Colonel Fowler, was killed. After this siege, the 156th was relegated mostly to garrison duty where the men lived and worked in close, unsanitary conditions where diseases, insects, poor sanitation and contaminated water added to the misery the soldiers endured.

Typically, unsanitary conditions lead to contamination of food and water with feces, which is why today there are “Employees Must Wash Hands” signs in restaurant bathrooms.

During the Civil War period, one of the deadliest of these feces-borne illnesses was dysentery. Dysentery caused a painful inflammation of the colon. Individuals who contracted this bacterium would experience severe stomach cramps accompanied by violent bloody diarrhea. Soldiers often died from its complications.

Private Michael Malady developed symptoms of acute diarrhea in late July 1863. When the misery did not abate, he was sent to the hospital located in Baton Rouge. Private Malady remained at the hospital for only a few hours before he died.

Private Malady was interred in what later became the Baton Rouge National Cemetery in 1867. About a month after his death, The New Paltz Times ran Private Malady’s obituary. It listed the cause of death as “dysentery in its worst form.” The reporter continued, “he leaves a wife and eight small children to mourn his loss.” They also informed their readers that the family would “need assistance.”

Shortly after the death of her husband, Bridget relocated from Gardiner to Broadway in the City of Newburgh. Roughly five years after her husband’s death, Bridget Malady applied for a widow’s pension from the Federal Government. Application 161107 was approved and given the pension certificate number 190491. This would have helped her make ends meet.

By 1880, she lived with her son John at 387 Broadway in Newburgh. John died in 1892. After he died it appears that Bridget left Newburgh for New York City, where she died around 1900.

For more information, contact the New York State Military Museum.