Have you ever tried to dig a hole in your Gardiner backyard and marveled at the effort required to scrape deeper and deeper into the dense clay soil? Or maybe you live on one of many properties plagued by standing water after heavy rains, the puddles blocked from percolating into the Earth by the same thick layers of clay.

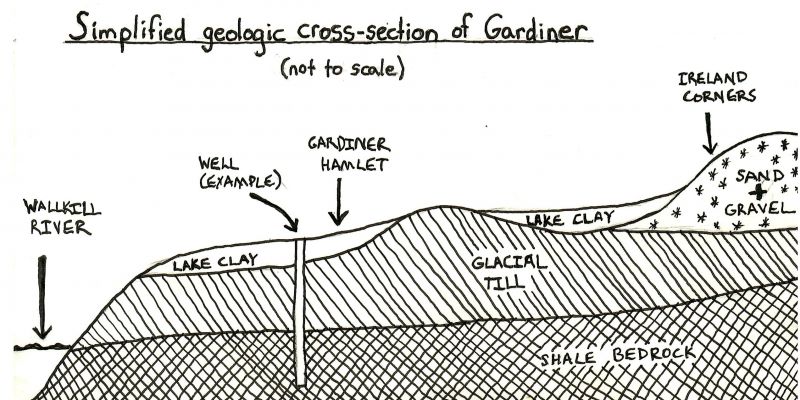

How did Gardiner come to be gifted with (or cursed by) such dense clay soils? To answer this question, we must go back about 15,000 years to the end of the last Ice Age, when the glaciers that had filled the Hudson Valley were melting away from south to north. Torrents of sediment-laden meltwater poured off the ice sheets and turned the Wallkill and Hudson Valleys into vast lakes, their waters blocked from draining south to the Atlantic by piles of rocks and debris (moraines) deposited by the retreating ice. As the centuries rolled by, the sediment suspended in the meltwaters of these lakes settled slowly to the bottom, forming a layer of clay over the rubble (or till) left by the receding glaciers. When these lakes finally drained, the land that would one day be called Gardiner lay draped in a mantle of this lake-bottom clay. Over time, shrubs and grasses colonized these dry lake beds, followed by trees and eventually humans: but the clay remained. These are the “Churchville” soils that underlie much of the Gardiner hamlet and surrounding areas.

When humans began to farm these old lake beds thousands of years later, they found that, despite the poor drainage, the soils could be productive for hay, pasture, and some vegetable crops – indeed, they are classified today by the USDA as “prime farmland soils if drained”. And speaking from personal experience, it is possible to have a productive backyard vegetable garden in these soils with proper attention to drainage and amending with organic matter.

Not everyone in Gardiner lives on these clay lakebed soils. In some places on the landscape, such as slight rises and ridges, the lake bottom clay did not collect as thickly and the underlying glacial till is close to the surface. These soils drain much better and are highly desirable for agriculture; a notable swath in the hamlet runs along the east side of Dusinberre Road from the fire station to Majestic Woods Drive.

In other places on the landscape, such as the deltas of the ancient streams that flowed into these meltwater lakes as well as along the former ice margins, the glaciers left huge piles of sand and gravel. The most extensive of these sand and gravel deposits lies along the Route 208 corridor, stretching from Forest Glen Road in the north to south of the Wallkill Correctional Facility. The soils that developed on these gravel piles are critically important for recharging Gardiner’s aquifer because rain infiltrates rapidly into them, replenishing the water-filled cracks in the deep shale bedrock upon which our wells depend. And finally, in the valley bottom of the Wallkill River run swaths of prime agricultural soil, rich in organic matter and nutrients laid down by countless cycles of river flooding, while along the base of the steep slopes of the Shawangunk Ridge lie shallower rocky soils studded with chunks of the cliffs that have fallen off over the millennia.

If you’re curious about the soils on your own property, visit the Gardiner Natural Resources Inventory, select the “Soils” map (#7) and find your property on the map. Some googling will yield information about the soil series, and if you’d like help interpreting the soil jargon – or to trade trips on gardening in our clay soils – feel free to send me an email at pannaria37@gmail.com.

Next time you’re struggling to dig a post hole for your new mailbox, take a break from cursing the clay and imagine yourself standing at the bottom of a frigid Ice Age lake that laps against the cliff faces of the Shawangunk Ridge, the water cloudy with drifting particles of clay, hulking white ice sheets looming just to the north. It won’t help dig the hole, but it might be a welcome and mildly mind-expanding diversion.