Fall is prime season for “choice edible” mushrooms—all except one, that is. The incomparable morel is the first edible of the year to ripen. Morel season peaks in the northern states around the second week of May, and Mother’s Day is usually the timing trigger for morel hunters.

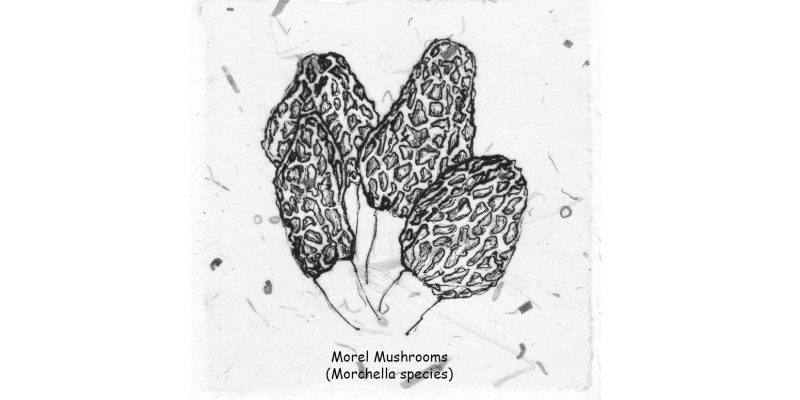

Arguably the most popular mushroom in the country, a recent internet search revealed no fewer than eight festivals devoted exclusively to morels. Morels are delicious to eat but difficult to find. You have to know not only when to look and where to look, but their mottled surface is camouflaged by the leafy undergrowth and, like black trumpet mushrooms, they can be nearly invisible.

Some mushroom basics are in order. First, though the study of mushrooms or fungi is included in botany books, fungi are not plants. In fact, genetically speaking, fungi are closer to animals than plants—both fungi and animals consume food from outside sources, whereas plants make their own food through photosynthesis.

Mushrooms, akin to flowers in the plant world, are referred to as the fruiting body or spore producer for the parent fungus. That is, they are actually just a temporary growth on a main fungal organism made up of growth called mycelium. If you’ve ever poked into a pile of wood chips, the white thread-like stuff is fungal mycelium, which lives hidden in the soil or inside of plants. The only visible part is the ephemeral mushroom—emerging for a time, to disperse fungi spores.

Morels were long thought to be saprophytic fungi (consuming dead plant material) but are more recently thought to be mycorrhizae (forming a mutually beneficial partnership with a plant’s root system). It’s also likely that they are both; many fall-ripening edibles such as hen-of-the-woods begin as parasites and, after the host plant dies, continue as saprophytes.

Morels can only be harvested from the wild, since thus far, efforts to cultivate them have failed, possibly due to the complex mycorrhizal relationships needed for their success. This has created a demand which commercial pickers seek to satisfy.

Studies have shown that harvesting mushrooms from the wild does not deplete future production. Harvesting wild plants on the other hand, can have negative impacts on sustainability. It’s not clear why this is the case, but it may have something to do with the fact that fungi can produce trillions of spores whereas plants only produce hundreds to thousands of seeds.

Mushroom hunters are still encouraged to follow good harvesting etiquette, and I offer three simple rules for the conscientious hunter: One…don’t over-pick. Even though mushrooms are sustainable, it’s polite to share the resource with others—and that includes squirrels.

Two…spread the spores. You can assist future production by using a porous bag or basket which will spread the spores while transporting a harvest. By the way, don’t use plastic bags to store mushrooms. They’ll get slimy, so stick to paper.

And the most important rule: tread lightly. The more serious transgression of commercial pickers is not over-picking a resource, but habitat degradation through disturbance.

Where to hunt for morels then becomes the question. Though morels have been recorded all over our region, Rosendale is a known hotspot. Though I’ve yet to substantiate this, Rosendale’s cement connection indicates a high calcium content in the substrates which are likely conducive to morel production. In any case, morels are known to associate with ash, aspen, elm and oak trees, living and dead, along with stream habitats. They also grow on sandy soils near streams. Further advice from morel hunters: once the first mushroom is located, slow down and search similar areas.

This May could be a good year for morels because of higher than average precipitation over the last year. We’ll see. Finally, in the interest of safety: get a good field guide, learn about the edibles and any poisonous look-alikes and, don’t eat any gilled mushrooms from the wild.