Food, clothing, shelter… and in the Mid-Hudson Valley: heat. There’s no escaping this part of life here, and as the age of cheap and available liquid fuels draws to a close we face both new and old methods for keeping warm. For a short, two generations we’ve become accustomed to the ease of cheap liquid fuels flowing from tank to boiler controlled only by the flick of the thermostat on the wall.

Now, many find themselves making the transition back to the solid fuel lifestyle and its requirements. And although most homeowners would LOVE to go green and have a complete, alternative-energy/thermal-retrofit for their homes, in rural Mid-Hudson Valley, wood is often the only sustainable and seasonally reliable source of heat that many can afford in the short-term.

The solid fuel lifestyle has its requirements: Skills (both new and old), labor and time, and a keen awareness, as it’s much easier to freeze the pipes, burn the house down, or combust your fuel poorly with a wood stove than an automated furnace.

STEP 1: Secure a firewood source, either your own woodlot or a close friend and neighbor with a large one, or order it from a supplier if you can afford it. STEP 2: Process your firewood – fell, haul, buck, split, stack. STEP 3: Properly store the wood to dry.

This last step is where most of us tend to go wrong. A stack of wood against the north side of a house with a tarp over it is an ideal way to grow mushrooms, but it won’t yield wood fit for your stove. The following is an overview of why it’s hard to dry wood well and what it actually requires, putting you one step closer to local self-reliance.

Burning green wood (more than about 20 percent moisture content depending on species) is a bad idea, although many do it year after smoky year; it promotes creosote build-up in the chimney which can cause chimney fires, is hard to keep ignited (while at the same time keeping air flow through the stove to a minimum), reduces heat output by 20 to 70 percent (causing one to need about one-and-a-half to three times as much wood for the same amount of heat), emits much more air pollution, and is heavier to process.

Under average conditions it takes a year or more to dry 16-inch cordwood thoroughly. Remember that wood only really dries in New York State between April and November, when temperatures are above 40°F and humidity levels are relatively low. Even with a well-sited and built wood stack, most of that drying occurs between July and September. A good wood shed also does most of its work during that optimal period, but can achieve some degree of drying all year long.

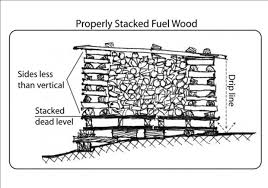

Proper construction of your firewood stack (you’re crafting a stack not making a pile here) involves the same things as any building: a stable foundation with air access underneath, stable shape (not too tall for the width), solid connections (the way the wood stacks against itself) and a sound roof, basically anything impervious, large, flat and rigid, like scrap plywood or, best of all, scrap metal roofing, pitched away from any area that would backsplash water on to the wood. I usually don’t recommend tarping, as it is so hard to keep the wind from removing or misaligning a tarp and snow from forming depressions in it so that water slowly percolates into the pile. If you must use a tarp, heavy canvas or rubber tarps are best.

Ideally, you burn the top three-quarters of the pile and then restack the remaining one-quarter on top of another stack for the following year: Stack, Cover, Dry, Burn, Stack, Repeat. Enjoy.