One mark of good writing, I believe, is writing that makes us interested in something we’re not interested in.

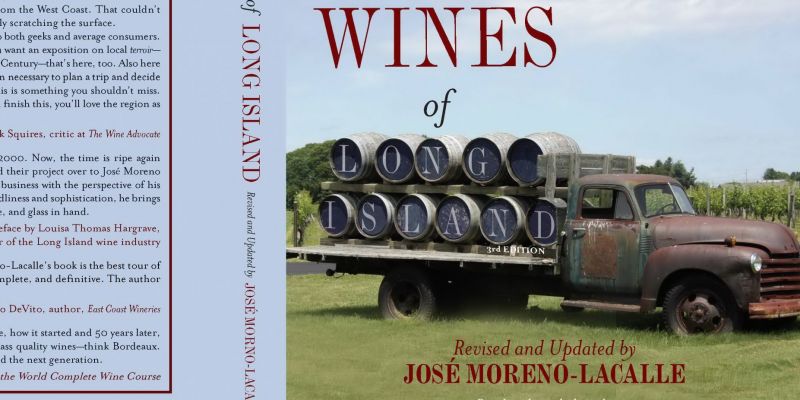

I opened Gardiner resident José Moreno-Lacalle’s book, The Wines of Long Island (3rd Edition, based on the 2nd edition by Edward Beltrami and Philip Palmedo), expecting to skim a few pages and write something brief. It looks much like a coffee table book—for looking, not reading—and the cover says, “A must-read for anyone visiting the wineries of Long Island,” which I have no intention of doing. Also, I’m interested in wine only to the extent necessary to get a glass into my hand on a Friday night.

By page five, I realized that I was actually reading (including all of the foreword, the preface and the introduction). By page 19, I was getting impatient to start skimming. By page 30 I surrendered, and settled in for a long read.

Ostensibly, The Wines of Long Island is about wine. What made it hold my attention, was its many small epiphanies on a much broader plane. In the chapter on the recent push for sustainable, “natural” wine growing, a vintner notes that “farming itself is not natural.” What was I thinking? Of course it’s not. In nature, seeds blow where they will; grow if they can; die if they can’t. Farming, the vintner goes on, “represents a massive intervention in nature.” In viticulture this extends even to the space between the vines and rows; the leaf canopy of one vine must not cast too much shade on the other.

When the book tells us of the many awards—in blind taste tests and international competitions Long Island wines frequently beat “super-premium” California and French wines—it’s easy to raise an eyebrow. Surely someone is spinning this a bit; if something is so good, why isn’t it in every shop and on every restaurant menu with those French and California wines it’s supposedly better than? Well, Long Island is tiny, with a wine growing region that can produce 400,000 cases of wine a year. One producer alone in Burgundy, France, produces the same. California’s Napa Valley produces 9.2 million cases. So while the quality is there, Long Island wines simply can’t be ubiquitous.

The Wines of Long Island also has its share of charm; 20th Century British writer Alec Waugh is quoted as saying, “At the age of 20 I believed that the first duty of a wine was to be red, the second that it should be Burgundy. In 40 years I have lost faith in much, but not in that.”

While I was deep into reading the book, my husband and I went to Gardiner Liquid Mercantile, where I asked for any full-bodied red. Coincidentally, Wolfer Estates 2017 Table Red is what I was poured. That red, possibly my first Long Island wine, was very fine indeed, and Wolfer Estates, in Sagaponack, Long Island, figures heavily in The Wines of Long Island, so it felt like a surprise visit from an old friend.

My plan is to head over to The Hudson Valley Wine Market in Gardiner and see what Long Island wines Len has. I have a lot of catching up to do.

The book is available from Banner Bookstore in New Paltz, the Gardiner Library, the Elting Memorial Library in New Paltz, and online at Wine, Seriously (https://blogwine.riversrunby.net).

Editor’s Note: José Moreno-Lacalle is a member of the Gazette Editorial Committee